Charge: a fretful turn of mind and attempted pessimism. Defendant pleads guilty.

Defendant: “It is hard, yes, insuperably hard to be a good pessimist. You might as well not try.

“A pessimist should be bitter; pessimism is a bitter creed. A pessimist should despise hope, not because it is worthless, but because it is meaningless. A pessimist, I say, should be rational, high-minded and grave, for a pessimist should respect his creed, he should believe it and defend it! But such is so seldom the case. How hard it is for a mortal man to be a good pessimist!

“It is easy to always predict the worst, but the worst so seldom comes. “The dinner will burn, the shower will break, the cat will die!” clamours the ordinary pessimist, amidst his ordinary, uneventful life. Very little of it actually occurs. When it does occur, what does he do? Shrug his shoulders like a philosopher and say, ‘the worst is yet to come’? Take note, calculate the frequency of such events, to aid his future predictions? Yes, he shrugs alright, and he forebodes, but he means nothing of it. The mishap means everything to him – it comforts his heart – he gloats – he actually takes joy in the success of his prophecy! He calculates too, but always on this principle: a mishap once, a mishap always.

“The truth is, he is hopelessly optimistic. He thinks he can go about predicting every possible ill, and that everything will bow to his narrative. If he is right once a week, he is satisfied that he knows the truth about the universe – or rather, about toasters and showers. Ha! The truth is bitter. The world is not so kind to the pessimist as to be genuinely, unremittingly evil. And when things do go wrong, the poor pessimist has unwittingly deprived himself of the very thing he aspired to: the ability to suffer. He can only acquiesce in evil; it is nothing to him. He loses nothing good because he expects nothing good. The optimist suffers more.

“But the very fact that pessimists have descended to such expedients is a cause of shame and embarrassment to me. Noble, hard-won pessimism asserts that the toaster can break if it wishes, or not, if it doesn’t, and none of it matters. A working toaster is as bitter a fact as a broken one. ‘For the days are evil’.

“But if the world is evil, if there is a demon for a God, what would it matter? Evil would no longer be bad; it would simply be true. What reason would we have to complain? We would have no values – or we would have the wrong ones. The only way to true, deep pessimism is to believe in a good God and believe there is no hope since he has failed. But I do not believe that.

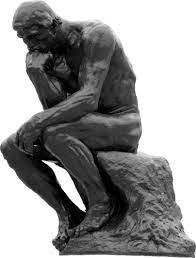

“So I come at last to acid truth: petty pessimism is petty, deep pessimism is not deep. And there go some of the best things in life! The Norse warrior, dying with his back to the mountain, hopeless, laughing, taken for his heroism to Valhalla, so that he might die once more at the End of the World – horrible, isn’t it? Yet how noble! That man sought honour for honour’s sake, not even so that he could enjoy it. Yet he was wrong. And the mystery of all it is that even if he was right, the truth is, he laughed: this, the icon of pessimism, was not a pessimist. He knew he had the best lot by far. He was happy, for he would gain his heart’s desire.

“Pessimism is doomed, and that is a tragedy.

“I have failed. I no longer care what my sentence is.”

As I listened to this trial, I felt deeply moved. I think this man has grasped something very deep. I reflected, puzzled, that Christianity is marvelously optimistic – it claims that the Highest Power will make all things good and offers goodness freely to all. But the nobility of the Norseman has not been lost. More noble was Christ, who wept, who sweated great drops like blood, praying that that his cup might be removed, knowing for what purpose he had come.