[At length, after an absence doubtless not unwelcome, the historian whose heavy hand is responsible for the preceding posts returns, with five weeks’ worth of writing. If he had the opportunity, no doubt, he would completely rewrite the remainder of this Chapter. As is, he must settle for some brief explanatory remarks. The first is that they are largely concerned with what in despair he has decided to call science, though, in fact, as often as not he is concerned with a misconception of science. The reader will not doubt that he has a hearty fascination with the natural world and a clear conviction that it operates according to natural laws; but they will equally realise that he deeply disagrees with the philosophy of Dawkins. He can only plead that the scientist he is writing about did too; and that, as his account of the scientific revolution should show, Dawkins represents only a branch of a branch of scientific philosophy. The second is a philosophical matter. The author’s opinion – so far as I can get it from him – is that we talk too much about ‘science’ in the abstract; and though here he has faced the word directly, and endeavoured to demonstrate its complexity, he thinks anyone wiser than himself would have taken a more roundabout route, by leaving the word science be, and discussing wisdom or curiosity or precision instead, until the idea of science sprang up spontaneously in their mind, without any of the baggage we have hung on it by long usage. The last is a caution. If this section errs, it errs into unclarity. He therefore considers it best that the following five parts be taken together, as one continuous argument, rather than a series of independent essays. And finally, now that he has unburdened his mind from the troublesome task of thinking about science, he has fallen into a deep slumber.]

There are two possible reactions to the foreign quality of Browne’s science. The instinctive response is to suppose that it is not wholly scientific. I suggested, above, that Browne’s science seems to us misguided, when I said that it is unlikely to be misleading. Now it seems to me that his image and opinions of science are not only interesting and stimulating, but positively instructive, and in that capacity important. For the other way we might react to the strangeness of his science is to infer that our own understanding of science is somewhat awry.

This topic will take us into the whole history of the scientific revolution, but that will hardly be a digression. That is, after all, Browne’s immediate context; and he is himself a player in that revolution. Hence some clarification of what science is will help, not only in the study of the man, but also in the study of his times.

The word science is loaded with connotations of a kind that make it dangerous for use in history. It obscures matters, not by being vague, but by being concrete. There are words like ‘faith’ that conjur up only vague images and meaningless, contradictory overtones, but that is not the problem with ‘science’. ‘Goodness’ has always had a hard time defining itself, though it has at various points in the past it has met with some success; in the modern world it has finally given up and settled on retaining one concrete meaning to keep it in business, in the vulgar line of food advertisement. But ‘science’ is not afflicted by this vagueness. We know exactly what science is. We can picture it: and we frequently do. We picture it every time we contemplate the real world. Science, to our understanding, is modern life.

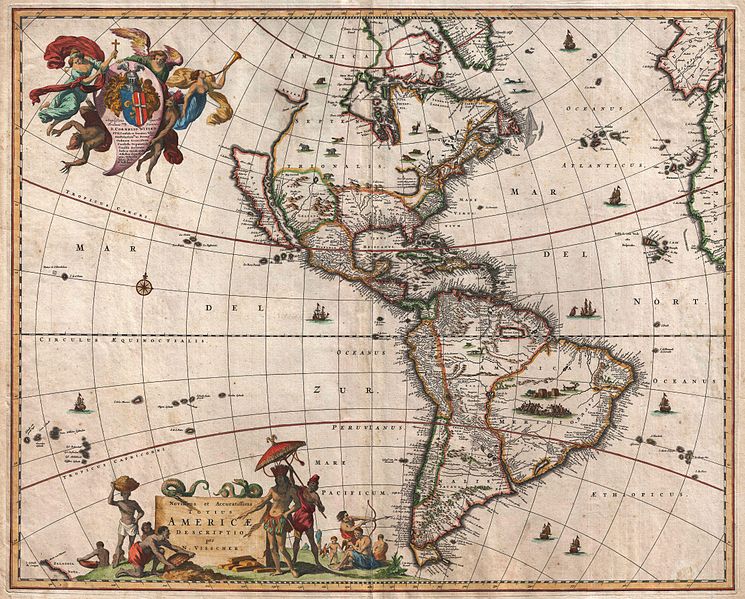

And our picture of it is beyond belief; it is as wild as the wild utopian visions of an imaginative medieval man. Imagine him, as he imagines you: he sits in his stone cell, with a goose feather in his hand, and his trusty iron-gall ink at his side. He has a lump of coarse bread in front of him, though he is too rapt with his fancies to eat it. He is on a wooden stool with a wooden desk and his light is a little candle. There is nothing remotely modern within sight. And this is what he imagines.

‘First: in the world of science, in the future paradise of knowledge, there will be a marvellous renovation of the matter of things. Buildings will be wrought, not of stone or wood or iron, but of secret compound substances the which are most pliable and sturdy, and whereof there shall be no lack. Clothes, likewise, shall not be in dearth, for magic and scientific arts shall have discovered a means whereby fabrics marvellous light and fine shall be had in good supply. From fire, whereby innumerous accidents and tragedies have oft befallen man, shall the danger and labour be disengaged; whereby light and warmth shall be provided at small cost. The life of the sage shall be enlightened and easy, for there shall be nothing in want but the new arts shall amply provide: when he riseth, no servant shall be needed to cook his breakfast or brew his coffee (for coffee and tea and spices and all such luxuries of the east shall be transported by swift means beyond the device of our imagination), but he shall have them. His chariot shall need no horses, but shall be motive through a swiftness wrought within it. His tower, wherein he shall labour, will he ascend without stairs, but by rapid and automatic ascent, so completely will he have harnessed the powers of nature; and all the day shall he pry into the secret and mystical cyphers and numerics whereby the natural forces of the world are ordered. All things that now must be done by man or beast will in that time be accomplished by ingenuity, and nothing shall be debarred from the wise and blessed people of that age: they shall raise themselves aloft in flight and descend to the depths of the ocean.’

This – and much more like it – is what our inspired monk dreams of, as the extreme end of the arts of knowledge – what we call science. This, to him, is its utmost perfection. It is a portrait of the life of a modern drudge in an office. It could well be an accountant.

That is what we mean by science: everything that makes modern life modern; and everything that premodern life lacked. Science, in our minds, is essentially synonymous with 21st century enlightenment. To the medieval man, scientia meant nothing more than specific than ‘knowledge’; and though like all words it has passed through various meanings, its present use is almost ferociously literal. A simple enumeration of human knowledge shows that. We all know that the natural world is the basic subject of science; and we now think we know, in varying degrees of detail, everything from one end of the physical universe to the other. All technology is attributed to science; thus science includes what is man-made as well as what is natural. The present state of morality and religion owes itself to science: so every agnostic or atheist, and most believers too, are convinced that their beliefs are scientific. All rationalism or enlightenment is thought to be scientific, for it is generally believed that before science all thought was simple, superstitious and strange. Indeed, there is a current vogue in what people used to call primitive superstition; and it owes itself to the collective realisation of Western people that they are not simple, superstitious or strange enough themselves. They may talk unscientific, but at the end of the day they still think that science is plain fact. Let us take even the opposite of science; surely the humanities deserve that title. But history, in today’s books, is scientific history, and a belief has gotten around in the philosophy departments, that philosophy, which was once the handmaid of theology, is now the handmaid of science. With so long a train it is a wonder that scientists still talk about progress. It is a heavy weight to drag.

But if everything modern is governed by science, it is not because science is a broad concept. It finds its way into all modern knowledge, but it does not mean simply intelligence. It means a particular kind of intelligence – a certain way of thinking. Consider what we mean by the word ‘scientist’. Though science is the guiding principle of all modern knowledge, not all modern people are scientists. ‘Scientist’ means someone completely guided by empiricism, and impervious, in their official capacity, to emotions and philosophy. It means someone who is systematic and theoretical, whose habitual thoughts are so technical as to be beyond the comprehension of most mere mortals. It means someone who works in a laboratory and studies things so microscopic that ordinary people are not even aware of their existence. It means someone who operates in an array of very rigidly defined Latin terms, or in figures and formulas wherein Greek letters outnumber Arabic numerals. That is our modern opinion on what a scientist is, and because it is modern, we consider it a scientific image of what a scientist is. Consequentially, there is a vague notion around, that science, in our overweening sense, was developed by such people as these. Which, as it happens, is not true. The current breadth of knowledge owes itself to a most motely crowd of individuals, few of whom fit that description. The current ingenuity of technology owes itself to many who do not fit that description at all. So long as we think of science as simply that, a great many who had the intellectual virtues that won us our modern knowledge are dismissed as backward and antiquated. For we consider a person of the past enlightened in so far as they share our worldview, which is itself a harsh and fruitless standard; but for a scientist of the past to be enlightened, they must also fit our image of scientists, which is so brutally specific.

This view of science, and this way of judging scientists, I think, does really exist, which is in itself astonishing; particularly as it exists amongst historians, who of all people ought to oppose it. It is a view that creates a terrible sense of historical claustrophobia, and suffocates the life of the past; and among the unwary it has been suffered to suffocate discipline of history. When the present is used as an absolute measuring rod for the past, it is impossible to learn real lessons. If all modern thought is scientific, then is to the present that we must look to learn science – not the past. And since science means ‘all that makes us enlightened,’ that is a severe restriction on the lessons to be learnt from history. If science is the present state of things, in matters of nature, technology, ethics, religion, scholarship, and philosophy, what can the past teach us? The only ideas from the past we will approve are those that bear resemblance to our own: if our world and worldview is enlightened, then worldviews unlike ours, in the past, must be unenlightened. The only lessons we will be willing learn are the lessons we have already learnt. All the lessons of history will be old lessons, and that means outdated lessons. For it is a profound and terrible truth that if you want to believe in history, you cannot believe in yourself; and a scientific society establishes itself upon a smug self-confidence. To be sure, there is a current reaction against this, which we shall return to in the course of our discussion. For now, we are simply concerned with it as it affects our understanding of the scientific revolution, and more specifically Sir Thomas Browne. And this is the essential principle, without which it is impossible to understand the past: that if we want to learn anything from history, we must get out of our own heads. We must take a broader view of enlightenment than we are used to. We must be take a more scientific view of science.

It is impossible to deny that if we judge by this standard of enlightenment, Browne is not noteworthy at all. He is a century behind the best of his generation on the points that matter most to us, and his methods are as far from our own as one could ask. At best he is a half-committed cousin of Kepler and Galileo, for he is certainly not in their league; and in a revolution it is the half-committed on whom the judgement falls heaviest – and the guillotine. Fortunately the modern historian is rather more sparing than the Jacobin: though we might idly regret the consequent insipidity of modern history books. At worst, the critics first praise his modernity and then castigate him for not being modern enough. At best, they treat him as essentially ignorant and backwards, and then praise the flashes of enlightenment that occasionally break through. At any rate, all are agreed in considering him little more than a curious mediocrity.

Indeed, Browne suffers more from our standards than most of his other great contemporaries. Take up the comparison, or rather the contrast, with Galileo, and the point becomes clear. All that is best in Galileo is still approved today. A great deal has been added, much, perhaps, superseded, but in spirit he is still considered basically praiseworthy. It helps that we give him a selective hearing. What his views on chemistry were, I do not know; it is almost certain that they were cruder than our own. What his views on religion were, I do know: and they are definitely more Catholic than our own, and in some senses more medieval. But these do not matter to us. He did not set up as an expert on chemistry or Catholicism. It is his astronomy that is important, and in astronomy he really was moving towards modern views. It is his physics that matter, and in physics he really was progressive.

The case is different with Browne, simply because there is almost nothing in common between Browne’s project and Galileo’s. They are both part of the scientific revolution. They are both revolutionaries, but they stand for two different revolutions. They almost stand for two contrary revolutions, whose successful union is as surprising as the other great union of the day, the union of England with Scotland. Both revolutions were necessary for the creation of modernity. Galileo stands for one revolution: a mathematical revolution in scientific theory. Browne stands for the other revolution: the revolution in research.

As a mere matter of gratitude we might consider all who contributed, whichever half of the revolution they participated in, as scientists; for what we mean by the scientific revolution is that swift and sweeping change that gave us the knowledge that makes us modern. And it is more than a mere token to call people scientific who carefully and earnestly pursued knowledge, and men like Browne did every bit as much as men like Galileo. But it is pure laziness if we do not make an effort to understand both sides of the revolution. Before concluding that Browne is a half-baked scientist, because he read Aristotle and Galen as well as cutting up cadavers, or because he did not make such sensational discoveries as Galileo, and in general did not meet our modern standards, we have to ask whether he would have wanted to meet our standards. ‘Science’ meant something different to him than it does to us; and rather than hurrying on with the assumption that we know better than him, we might take the time to consider what, in his time, science really was. Then we can start asking whether it was better or worse than our own science. Not before.

ilton: Paradise Lost

ilton: Paradise Lost

oethius: The Consolation of Philosophy

oethius: The Consolation of Philosophy

reface to a Project

reface to a Project