This idea is long become stale, that there are ‘humanities’ minds and ‘science’ minds. It needs some reworking. Such a distinction has not always been made, and even now that it is made, it is not always applicable. Nevertheless, if there should be a divide, I am land the humanities side.

But there is a kind of science that can only be practiced by those with an ‘arts’ turn of mind. Ironic we would be if we called it ‘pseudo-science’ – but then, we shall be ironic. Pseudo-science is the rational attempt to make sense of the world as we observe it using primarily reason and such equipment as exists in our minds. It is therefore the contrary of science, which makes sense of the world by experiment and further observation.

To give a very basic example, we observe that the moon always shows us the same face, though it is variously shaded at different times of the month. The scientific method would proscribe a mathematical calculation of the rate at which the moon spins, conduct a series of observations and perhaps recreate the situation in a lab and draw its conclusions therefrom. The pseudo-scientific method, on the other hand, proscribes philosophical analysis along the following lines. The chances of the moon fortuitously always presenting us with the same face are so small as to be negligible. Yet we know that it does, and so it must do so for a reason. It is already known that the heavenly bodies obey the same laws as the earthly, though on a greater scale; for instance, gravity on earth draws French aristocrats’ eyes down their noses, but in space it draws planets into orbit. The closest parallels we have on earth to our lunar phenomenon are (a) two objects tied by a string, which when whirled always face each other in the same way; and (b) double-sided fridge magnets, which are only attracted to the fridge on one side. Now, no string is observed to attach to the earth, and indeed it would be impossible, for such a string would knock pedestrians off their footpaths, which does not happen. Ergo, the moon must be a giant magnet, with either the positive side facing earth’s negative side, or the negative side facing earth’s positive. A neat bit of reasoning, and thoroughly unscientific.

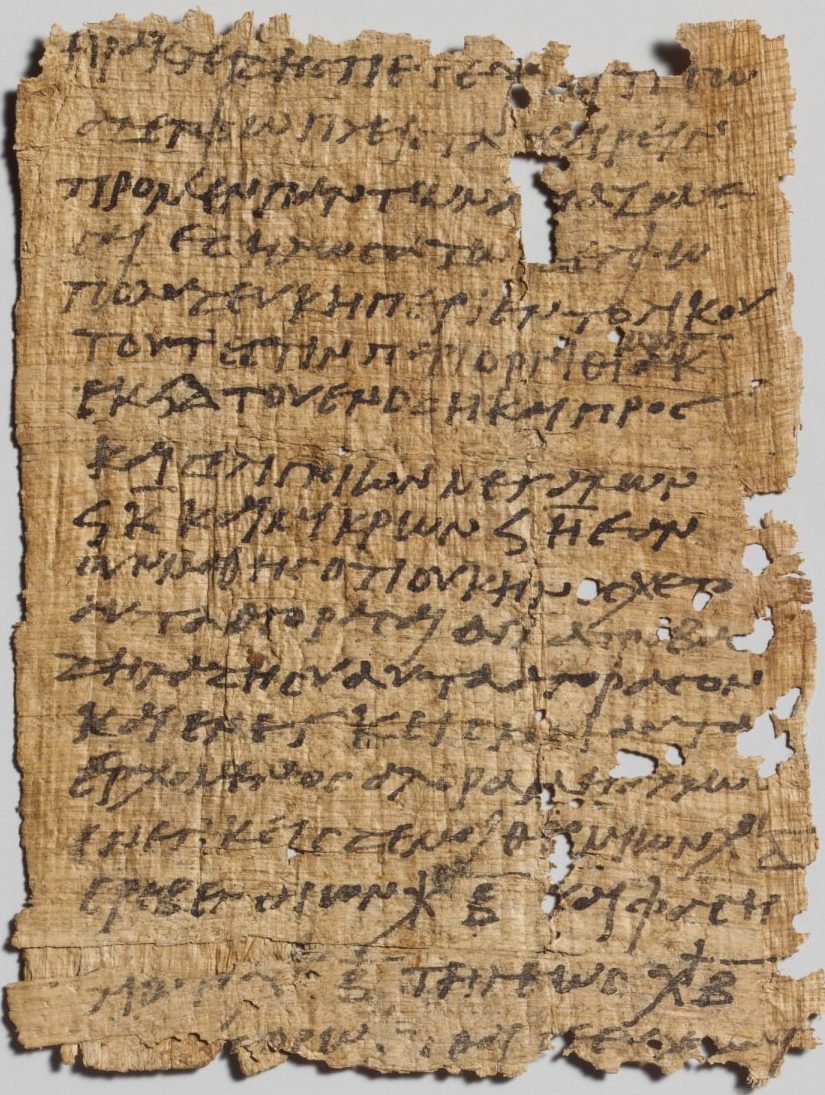

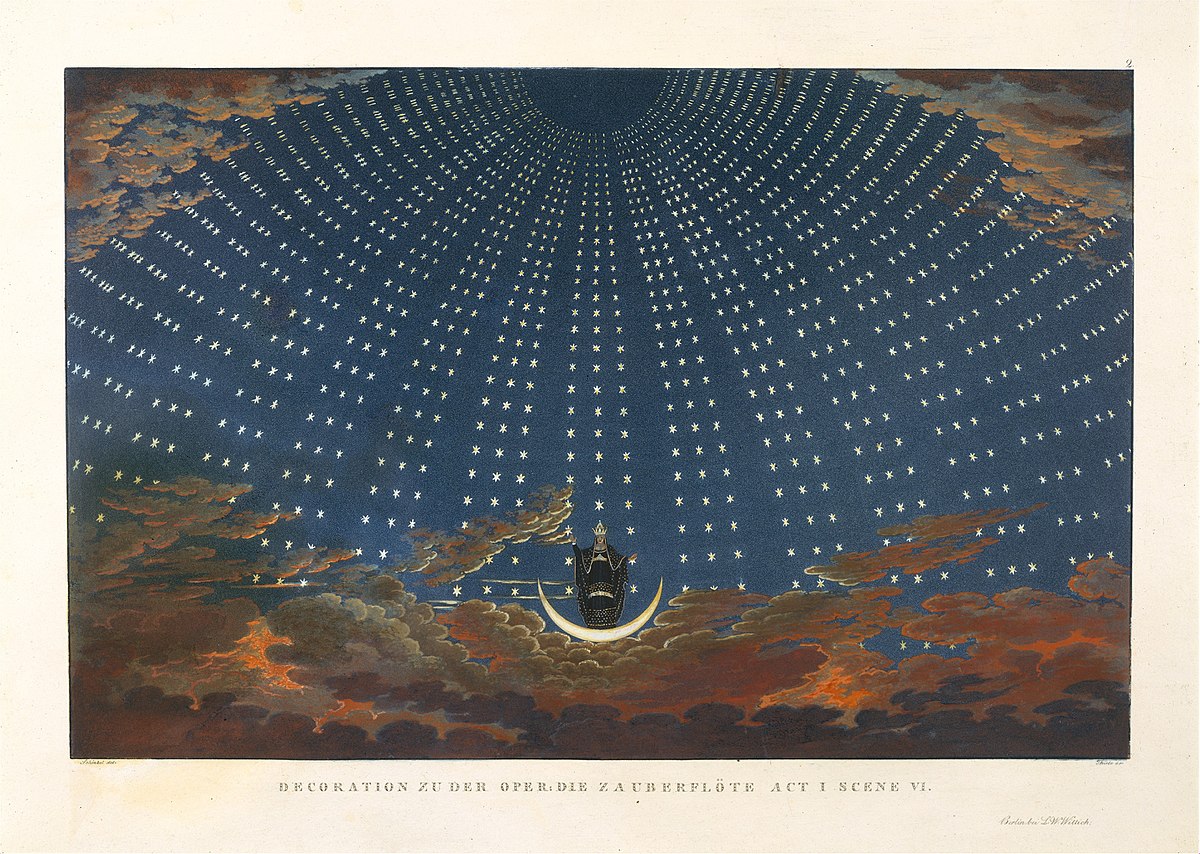

In fact, pseudo-science predates science. Thales, who went spouting so-called ‘nonsense’ about all being water and rocks having souls, was not, as is often said, the fathers of science, but if anything the father of pseudo-science. Actually, it predates even him, but he is the first convenient name we can latch onto. The history of science was mingled with the history of pseudo-science until relatively recently: one can see this by simply looking at all the big names. Pythagoras, who had a theorem (as did many others), also had the notion that there are 183 worlds, arranged in a triangle. His proof is lacking, but doubtless it was of a similar kind to his proof that respiration is a prerequisite for life – which he never claimed wasn’t obvious; after all, it’s all common sense and reason, isn’t it? Plato encouraged his disciples to study the heavens geometrically, but he also figured that the planets must make huge sounds, since they are so big and move so fast, and dabbled in reasoning out the explanation for why we can’t hear them. His best answer was that it is because they make a harmonious music which our ears are so accustomed to that they no longer hear it. Ptolemy with the aid of pseudo-science rejected the notion that the earth goes around the sun, and still made good astronomical calendars which were much appreciated.

Do you think this pseudo-science was a thing of the ancients? It was not. Galileo himself was a pseudo-scientist as well as a scientist. He knew, as all sensible people know, that the planets whiz around the sun in circles; he owed this idea to Copernicus. Johannes Kepler was not a sensible person, he was a scientist, so he decided that if the facts suggested that the planets go in ellipses around the sun, then that is what they do. But Galileo would not take it; his planets would have circles. Tycho Brahe, another scientist of note, had his own irrefutable and whimsically beautiful theory of the heavens: all the planets go around the sun, except the earth, which the sun itself goes around. Meanwhile, all these thinkers have added quite a bit more empiricism to their pseudo-science than their ancient predecessors. But they have not entirely relinquished the glorious heritage of pseudo-science.

Descartes is the last great pseudo-scientist, and those who wish for a clear and detailed example should study his cosmological views. Be careful, though, not to confuse pseudo-science with bad science. These are not mistaken experimental conclusions, though some of them are mistaken applications of Occam’s razor. Galileo thought the planets had circular orbits not because he made observations that mislead him into so thinking, but because he did not make observations, letting his reason run away with him. That is the glory of pseudo-science: the clear air of misguided rationalism.

Pseudo-science, which gives as much meaning to phenomena as science ever did, with not a fraction of the lab-coats and goggles! Safer, clearer, indubitable in the extreme – indubitable as only pure reason can be! Here is no less labour, no less intellectual humility, no less zeal for understanding than any scientist can offer, and far more interest, immediacy and illumination! Here is the poetry of the world, where science offers us its mechanics. Here is something as great as myth and fiction; greater, perhaps. For fiction tells us the history of worlds greater than ours, while pseudo-science tells us their natures; and while fiction does not pretend to reality, it is the pride of pseudo-science to arrogate itself to our own world, while its practitioners still admit, as humbly as anyone, that they could be wrong.

You will easily see, then, why pseudo-science exists at all. A world with no poetry to it is unappetising, so to speak, and pseudo-science, coming as it does from the human mind, has the power to make it poetic. Yes, God has made the world poetic enough, if we could only understand it truly, and every century we realise the moving power of the last century’s discoveries. But when discoveries are made, and often long after, they seem arbitrary and sometimes distasteful. And then there are the gaps which science has not answered… God alone understands fully the true poetry of the world. But anyone can understand the poetry of good pseudo-science, especially if it is convincing enough to seem true, but even, at a pinch, if it is simply make belief.

Perhaps that is why the ancient Greeks never discovered the science we now know: a world discovered by microscopes and telescopes and endless calculations was powerless to compete with their systems of simple maths, secret forces and anthropomorphic elements (that is, incidentally, a gross caricature, but it will do). Kepler and the men of his generation were only able to fully free themselves from its allure when they came to the conclusion that complex maths is poetic, or is itself poetry, so that discovering the world in formulae in no wise differs from discovering its beauty.

I hope, then, after all, it shall be clear that though I theatrically decry science, I can well admit that it has glories I do not understand, yet it should also be clear that though I have occasionally poked fun at the old ‘pseudo-scientists’, whom I admit were often (not always!) wrong, their profession certainly deserves respect and admiration. It is both noble and fun, an excellent philosophy and a wonderful joke. And if theology must supersede myth and science pseudo-science, it is not because the world is not as poetic as people have imagined it; in fact it is more so; and until we can fully understand it, perhaps even after, pseudo-science must live on with myth in our minds as we strive for truth, to remind us of that fact.