I am sometimes asked why anyone would learn dead classical languages. Practically the only reason that there can be is, for the books. If you would seek out what reasonable and eloquent people have to say in different places, there is no reason not to seek out what reasonable and eloquent people have to say in different tongues. In the Latin and Greek poets, the historians and philosophers, you will find humanity and wit, shrewdness and taste, as well as the folly and failings that mark men of all ages. A good language is good poetry, and good poetry in a good language is sublime. When you start reading Homer, you drink in the Greek as you learn the words and phrases, and as you progress you drink in the power of the poem itself. I have dipped in and out of various languages, dead and living, but that is always the mentality I have brought: though I might have enough philosophy in my own tongue, I can have more poetry in other tongues.

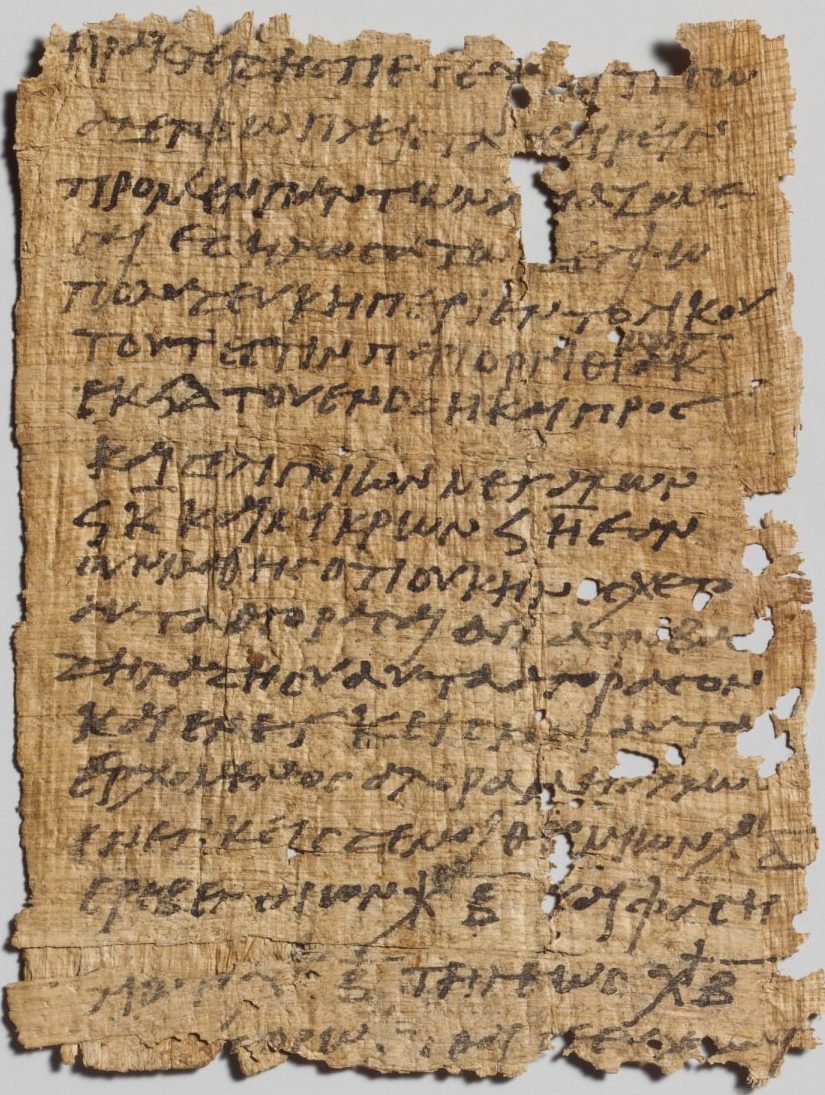

One of the greatest pleasures of reading other languages is the sight of the script itself. I could regale myself with a page of Arabic, though I could understand scarcely a word of it, simply puzzling out the phonograms and admiring the letterforms. Even before I could properly read Greek I liked the letters; when I read in the Vicar of Wakefield ‘Anarchon ara kai atelutaion to pan’ it took me a second to realise – and then I did – it was meant to be Greek, meant to be ‘ἄναρχον ἄρα καὶ ἀτελευταίον τὸ πᾶν’ – I nearly jumped out of my seat in dismay then, though I couldn’t understand half of it anyway! There was such a separation between the language and the representation, though the transcription was strictly correct and I do not think I have any rational ground for objecting to transliteration.

Some words sound natural and fitting, like the Latin ‘ruit’ with a rolled ‘r’ for ‘it collapses’, and ‘fractum’ for broken. Admittedly, many instances like this arise simply because a word in another language sounds similar to a word we use in our own language. It is always nice to recognise ‘πολύ’ (‘poly’) in Greek as ‘much’, though of course the only reason why that word should stand out is that there are many English derivatives. But why may we not enjoy such recognitions as much as genuine onomatopoeia? Of course, we must not mistake the one for the other.

Nevertheless, learning a language takes time, and when you can read a translation or bore your way through the original, it is often not only more convenient but also more enjoyable to read the translation. But the slowness of reading is amply justified by the pleasures of learning, the skills and breadth of mind gained, and the interest of coming into more direct contact with other minds that literally thought in different terms.

Ooooohhhh! Arkady, my friend…I would say I understand what you’re thinking, but being an Old Bulgarian I unfortunately think on a different plain.

LikeLike

Good sir, I do believe you need to edit your usage of the plane English with which you speak

LikeLike